After a cloudy and rainy day in Tucurui I continued my

tour in bright sunshine. It took me an hour and a half to get a lift

back to the place where I left my bike the other day.

As I open the window in the early morning I look into bright sunshine.

After two rainy days there are no more cloud to be seen, an absolutely

blue

sky. I pack my stuff and hurry out of the hotel.

It's rush hour in the jungle town, every few minutes a bus departs to

the

construction site on the river dam. I feel kind of out of place, I'm

the

only one in the overcrowded bus who doesn't wear blue working clothes

and

helmet. My presence serves as a welcome entertainment on the daily

routine.

From the last bus stop it's still a long walk and a short truck ride,

all

together it takes me one and a half hours to get back to the bar where

I

left my bike the other day.

"Oh, what a petty, you are back. I just wanted to sell your Bicicleta"

jokes

the nice owner of the bar, when I disturb his morning cleanup.

I ask if he already found someone to sell it to, but instead of an

answer I

he gives me a huge cup of Cachaça (the Brazilian type of rum), which

makes

it a difficult start at half past 7 in the morning.

I 'paid' the drink by leaving 2 or 3 kilos of food, noodles, rice and

soups,

as I already realized that I carry way too much. Therefore, I stocked up

my

water supply from 5 to 7 liters, which is enough for half a day or

so...

After a few minutes the town is out of sight. The next village, Novo

Repartimento, is approximately 70 kilometers to the south. "Novo"

(new),

because the old Repartimento disappeared in the waters of Lake Tucurui.

Nevertheless the inhabitants have been lucky, they have been relocated

before closing the dam. The natives who lived in that area have not

been

given that opportunity.

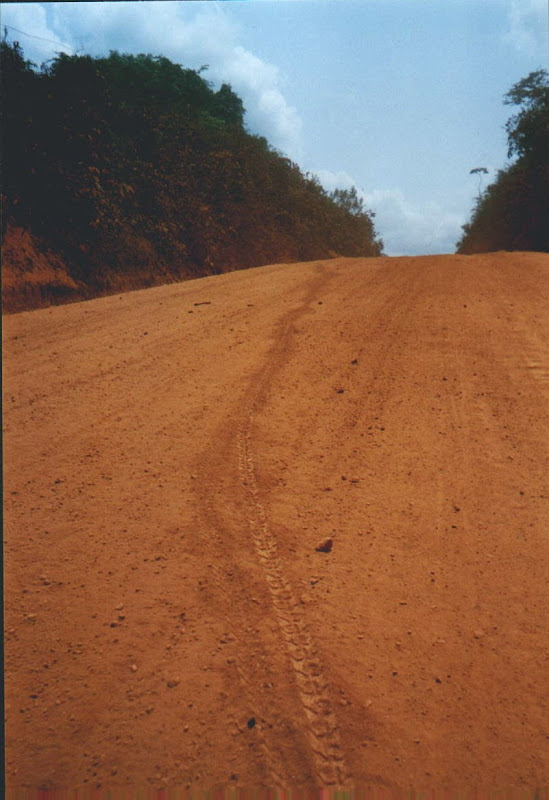

The road becomes more and more hilly, a constant up and down, mostly

through

uninhabited, native rainforest. Few vehicles use this 'shortcut', as it

is

much faster for the trucks to take another road down to Marabá, which

is 100

km longer, but on tarmac. That's why on the whole distance not more

than 3

vehicles pass by. And that is good for me, because the cloud of dust

emerging from a truck thundering by is enormous.

Occasionally smaller clearings appear, sometimes allowing a very nice

view

to the lake on the left, the rest is dominated by the green of the

forest.

The sun burned down, but I suffered less than the days before. Either

it's

better without the black

asphalt or I already got used to the heat.

The hills made it difficult to proceed. On the uphill part I often had

to

walk and on the downhill part I needed to pull the brakes as hard as I

could. I was not yet used to the dirt road and feared my bike would

brake

apart every minute.

In the afternoon I reached Novo Repartimento, and finally the BR230,

the

"official" Transamazônica.

There is not much sightseeing to do, the town seems to exist only to

supply

the trucks on the Transamazônica. It consists mainly of gas stations,

borracharias (tire repair shops) and basic restaurants. I have lunch in

one

of them, the usual, meat, rice, black beans and manioc flour, plus 2

beers

to celebrate the first 70 km on dirt.

In all of South America you won't find any bar or restaurant, not even

in

the most remote area, without a TV, and if there is electricity it will

run

on maximum volume. While I eat a soccer game is transmitted and the

restaurant is pretty crowded. The advantage for me is that I can

eat

in peace and do not have to answer a lot of curious questions, because

everything looks excited on the screen.

Only after the end of the game I am included into the discussions.

Which is

your favorite club and who will win this year's master cup, they want

to

know from me. Puuuuuh, perhaps I should have informed myself before

departure, I do not know anything about the current scores neither in

Brazil

nor in any other country. What a shame.

I now turned westward, and from here on there is much more traffic than

before. About every 5 to 10 minutes

a truck passed by, and each time I was covered with clouds of dust.

I spend the first night along the Transamazônica hiding in the woods.

The next days continued much the same: Hills, hills,

hills. Where did people get that idea of the "flat Amazon basin" from?

The hills are not very high, something like 50, a maximum of 100 meters

but

they are incredible steep, some of them more than 20%, I guess.

The guy who planed this road was probably no cyclist. (Besides that,

the

trucks have a hard time, too, climbing and descending all this hills.)

The

road is winding a lot, and it seems as if the road turns right or left

in

each valley just to pick up the highest hill available. I don't know

why

they made it like this, the landscape is not flat, but I see no reason

to

climb that much.

I go like this: Walk uphill, take a short rest, mount the bike, cycle a

couple of meters on the flat hilltop, then pull your brakes as hard as

you

can on the downhill, because otherwise you won't come to a full stop

down in

the next valley. And you have to stop, because down there you usually

have

to cross any old wooden bridge, which is better to walk. No way to built

up

momentum for the next uphill.

I stop at each shadow available to cool down and to drink some of my

hot

water... Every 30 or 50 km I pass a bar, restaurant or even a small

town

where I could get food and, even more important, cold drinks. I drink

an

average of about 15 liters a day: 10 liters of water, the rest is Coke,

Fanta, Sprite, Guaraná and lot of ice-cold beer :-)

The landscape is marvelous: Small farms spread over green hills, with

all

kind of fruits, the dense rainforest is never more than 200 or 300

meters

off the road. In this part of Brazil the land is owned by small farms

that

usually cultivate all they need for their own survival. It's not the

big

fazendas I've seen before, where you cycle along the same plantation or

cattle ground for hours, with big parts of the soil already deforested

and

deserted and "Private property" or "No trespassing"-signs posted

everywhere.

Here it's really cycling through thousands of beautiful tropical

gardens,

and once in a while stretches of native forest transform the road into

a

green tunnel.

Rivers and lakes were available whenever I needed

one, and I had a swim at least once an hour... I

usually preferred the places used by the locals, as I

don't know much about the dangerous beasts in there,

such as Jacaré (Amazonian alligator), Puraque (Electric Eel), Piranha and

lots more.

Once I cycled for a long time without passing houses.

I crossed one of these funny wooden bridges,

masterpieces of architecture where you never know if

you reach the other side alive. I stopped there, sat

down on the bridge with my feet bouncing down and just

asking myself if it would be safe to swim here when

I saw the two eyes staring at me: a big Jacaré, waiting for lunch...

I then didn't even dare to fill my water bottles, with

this scene of "Crocodile Dundee" in mind...

Night falls fast in the tropics. Within 5 minutes it's

completely dark, so you have to keep an eye at your

watch in the late afternoon. Instead of sleeping

somewhere in the forest I now often pulled into one

of these small farms to ask permission to camp on

their ground, and I was never sent away. I was ALWAYS

invited to come in, to have dinner with them and often

I was even offered a place to sleep indoors. I

preferred to sleep outside in my tent instead of

pushing the kids out of their bed, but I gladly

accepted the dinner, which was simple, but still better

than the rice with tomato soup I had with me to

prepare on my stove. (I 'paid' the food by

distributing cookies and chocolate to the kids.) The

houses had usually no electricity. A small candle was

the only light and water was picked up at the next river.

Road conditions worsened with every kilometer. The

problem was not that much the holes, stones and rocks

on the road. These were usually easy to avoid on two

wheels. The problem was the dust. Long stretches of the

road were covered with several centimeters of dust,

fine powder that spreads away like water when you

pass through. It entered everywhere, in each pannier,

in every plastic bag, into my food and into my lungs.

Together with the oil and grease it formed a perfect

grinding paste on the chain. The main problem was that

it formed a smooth surface, so I couldn't see the

rocks and potholes underneath. And I think I

don't need to explain what happened when a truck passed by....

Well, finally I reached the Xingu River, and some hours

later Altamira, the only town that rewards this name since I left

Tucurui.

The Xingu River is very beautiful. Clean water and -

at least at this time of the year - wide sandy

beaches. It is known for it's native population, with

one of the few Indian tribes in Brazil that

successfully preserves its own culture, and successfully

claims its rights from the Brazilian government.

Here in Altamira is an outpost of the "FUNAI", the

Indian administration office, which is frequented by

the natives dealing with bureaucracy or seeking health

care. I found them very fascinating. They walk around

in town like everyone else, go shopping and use buses

and taxis, but they walk around just in shorts, the

body covered with tattoos and paintings, and spears,

bows and poisoned arrows under their arms!! I had a short chat

with one of them, but I didn't dare to ask permission

to take a picture. When they finish their business

in town they go back to their villages along the

river, and while unsuccessfully searching for an Internet access I was

wondering if these guys need to care that much

about computers and the Y2K-bug...

Well, this was Rio Tocantins to Rio Xingu. Next part

is Rio Xingu to Rio Tapajós, 500 kilometers, where I

reach the next town of notable size, Itaituba.

Até logo

Micha

<-- continue part 3